I’m not sure what I expected the headquarters of a national organisation with the high profile of the Hepatitis Foundation of New Zealand to look like; perhaps not a nondescript brick former hostel in the suburbs of Whakatāne.

Many people are surprised when they find out, says chief executive Susan Hay. They think it’s in Wellington. “They ask, ‘What’s your address downtown?,’” Ms Hay laughs.

The fact it is in the Bay of Plenty is a historical accident. Whakatane Hospital lab technician Sandy Milne did his ground-breaking hepatitis B study in nearby Kawerau in 1984, and officially started the foundation in 1990. It moved into the 1960s’ era building, and it’s still here.

The location doesn’t make a great difference. “Logistically it’s about having enough nurse power out in the field,” Ms Hay says.

The foundation has 10 nurses working in the areas of highest need – Auckland and Northland, Rotorua to Hamilton, Bay of Plenty and East Cape, Napier to Gisborne and Wellington. They offer free blood tests and liver assessment, and provide advice and education, for patients and health professionals, including GPs; 22 staff are employed in Whakatāne.

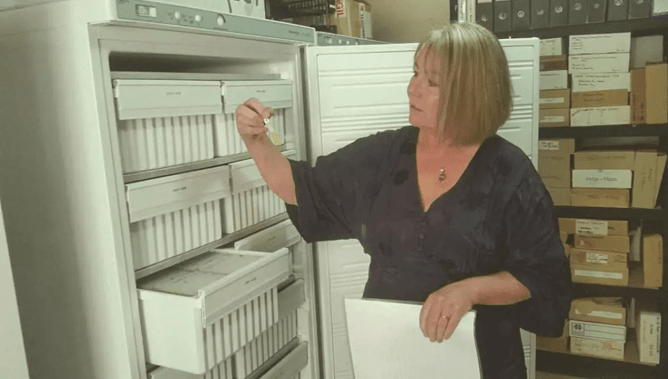

The building also serves as a repository for what Ms Hay calls its “treasure” – thousands of files and refrigerated blood samples collected from the time of the Kawerau study. Follow-ups and retesting of the original participants have made it the longest and largest study of its kind in the world.

Foundation board member and renowned hepatologist Ed Gane is among researchers using the resource in a search for a hep B cure. The DNA technology they can access barely existed when the first samples were collected.

Ms Hay sees the foundation as “guardian” of the material, until such time as a cure is found, perhaps in the next five to 10 years.

It’s fair to say hepatitis C has a much higher profile than hep B. Not only is it a disease rock stars die from (Lou Reed, David Bowie, Grant Hart), but the success with direct-acting antivirals means a cure is now available.

The gruelling interferon treatment of previous years is a bad memory, and a simple eight to 12-week course of funded Maviret (glecaprevir/pibrentasvir) can rid patients of an illness that may have tainted their lives for years. The Government has been quick to highlight this success and exhort GPs to get involved in prescribing.

Around 250 people a year die in this country from hepatitis B and C. While there is no cure for hep B, funded drugs can keep it under control, as long as those infected can be found and tested. An estimated 100,000 people are infected in New Zealand.

Hep B is now the main focus for the foundation. Last year, it put forward a national plan to tackle the disease, focusing on issues such as better education for GPs, better coding in online systems for monitoring, creating a “safety net for patients who fall through the cracks”, measurable targets and setting up a centralised register for patients.

Ms Hay says the Ministry of Health has not responded. She says her experience at WHO meetings has shown “you need to have a strategic national approach and a political will for managing eradication of viral hepatitis”.

“The focus from the ministry is they’re doing a national plan for hepatitis C, and there’s been quite a lot in the media about that as well, but there’s nothing about hepatitis B.

“It’s not about massaging the role of the foundation and keeping ourselves employed, it’s about what’s the best outcome for the patient, how do we reduce duplication, how do we work better across the sector.”

The aim of the national plan is to set up for when there is a cure, to make it easier to get people into treatment.

The foundation wants to get smarter about how it communicates with GPs and midwives; 74 per cent of referrals come from GPs.

The foundation receives $1.5 million a year in funding from the ministry, a sum Ms Hay says has not increased for six years. It doesn’t cover costs, so the budget is topped up with money the board makes from investments.

The challenges are already daunting, but the foundation struggles with lack of interoperability between IT systems and practice management systems (see related story, page 25).

The foundation has modernised its systems, putting everything into the cloud, so they can “talk” to other systems.

In a strongly worded submission to the Health and Disability System Review Panel, the organisation has called for government intervention in health IT.

“It’s not rocket science,” Ms Hay says. “We are such a small country, yet it is so difficult to get agreement to have repositories of information. People get very upset about repositories of information because of privacy, but if it’s to do with the care of the patient between the GP and perhaps the Hepatitis Foundation, then the information is well guarded.”

The foundation has 130,000 names on its database. Some are people referred because they had contacts with a patient, while 30,000 have the virus. About 9000 people are out there, probably under the care of a GP, but the foundation doesn’t know if they are being monitored.

Exciting times

Clinical director Alex Lampen-Smith says the past few years have been exciting times for hepatologists with the advances in treatment for hep C.

“It’s important to shout it from the rooftops,” Dr Lampen-Smith says.

Some GPs have been reluctant to get involved in Maviret treatment, fearing lengthy and complex consultations, but she stresses how simple it is; one consultation is usually enough.

It’s important to remind people that the B and C viruses are completely different, and hep C is “so much more straightforward” to treat, she says.

“We’re very excited about hepatitis C. But we don’t want to leave hepatitis B behind.”

Hep B drugs suppress virus

Pharmac removed restrictions on hep B drugs tenofovir disoproxil and entecavir last year, enabling GPs to prescribe them. The drugs suppress the virus but, if medication is stopped, it can “bounce back”. Monitoring is vital.

Dr Lampen-Smith says a lot of work is underway on a cure for hep B,but it is at an early phase. “This is a very hot area in international research. I think realistically – over the next five to 10 years – I don’t think we’ll be saying we’ve got a hep B cure in New Zealand inside five years. I think it’s going to be a longer pipeline than that. It’s a more complex virus in how it resides in the liver. Hep B is not as straightforward as hep C.”

Ms Hay says hep B incidence is down, although it is rising in certain groups due to immigration. Among Pākehā New Zealanders, it’s below 1 per cent, among Māori around 6 per cent and in the Asian population, 9 per cent.

It’s important to remember the human faces behind the thousands of files and blood samples stored at the foundation, she says. Nurses now see multiple generations of families. And some of the original Kawerau study participants have died from liver cancer.

After seven years with the foundation, and as a former Ministry of Health adviser, she feels it’s vital to be close to the grass roots of healthcare.

“As a bureaucrat in the ministry, you can lose touch with what’s happening in the sector. I truly believe that, when I look back at some of the programmes we were doing, primary care must have thought, ‘Oh, here comes another Ministry of Health official who doesn’t know anything about what we do.’”

The foundation has a good relationship with the ministry, although the tension over funding makes the NGO want to be as effective as it can be.

“Once you can show evidence to the ministry that, yeah, we are making a difference, you’ve got the mana then to say, we do need some more money.”

Eyeing the prospect of a readily available hep B cure at an acceptable cost in the next decade, Ms Hay says: “If we can have all these people ready for a cure...we can then shut up shop knowing we have done our job.”

In a nutshell

1984 – In a study led by Whakatane Hospital technician Sandy Milne, 93 per cent of the population of Kawerau were tested to ascertain the extent of hepatitis B infection. Nearly 8000 people were tested, and more than 500 were found to be carriers.

1988 – The government introduced a national hepatitis B immunisation programme for under-15s.

1990 – The Hepatitis Foundation was officially established as a charity.

2018 – Pharmac removed restrictions on hepatitis B drugs, tenofovir disoproxil and entecavir, enabling GPs to prescribe them.

2019 – Maviret, which cures most cases of all genotypes of hepatitis C, was funded and able to be prescribed in general practice.

– There is still no cure for hepatitis B. It is estimated 100,000 people in New Zealand have chronic hepatitis B.

Article published in July 2019 by NZ Doctor.